Before you read any further, first answer this question: who had (or will have) a higher carbon footprint at age 40, you or your grandparents?

If you live in the US and are roughly 40, like I am, the answer is your grandparents, and it’s not particularly close.1 My carbon footprint is about 15% lower than my grandparents’ when they were my age. In the UK, where the country’s last coal plant recently closed, the decline in per capita emissions is even greater - they’ve seen a 50% reduction in per-capita emissions since their emissions peaked in the 1960s. UK per capita emissions haven’t been this low since the 1850s!

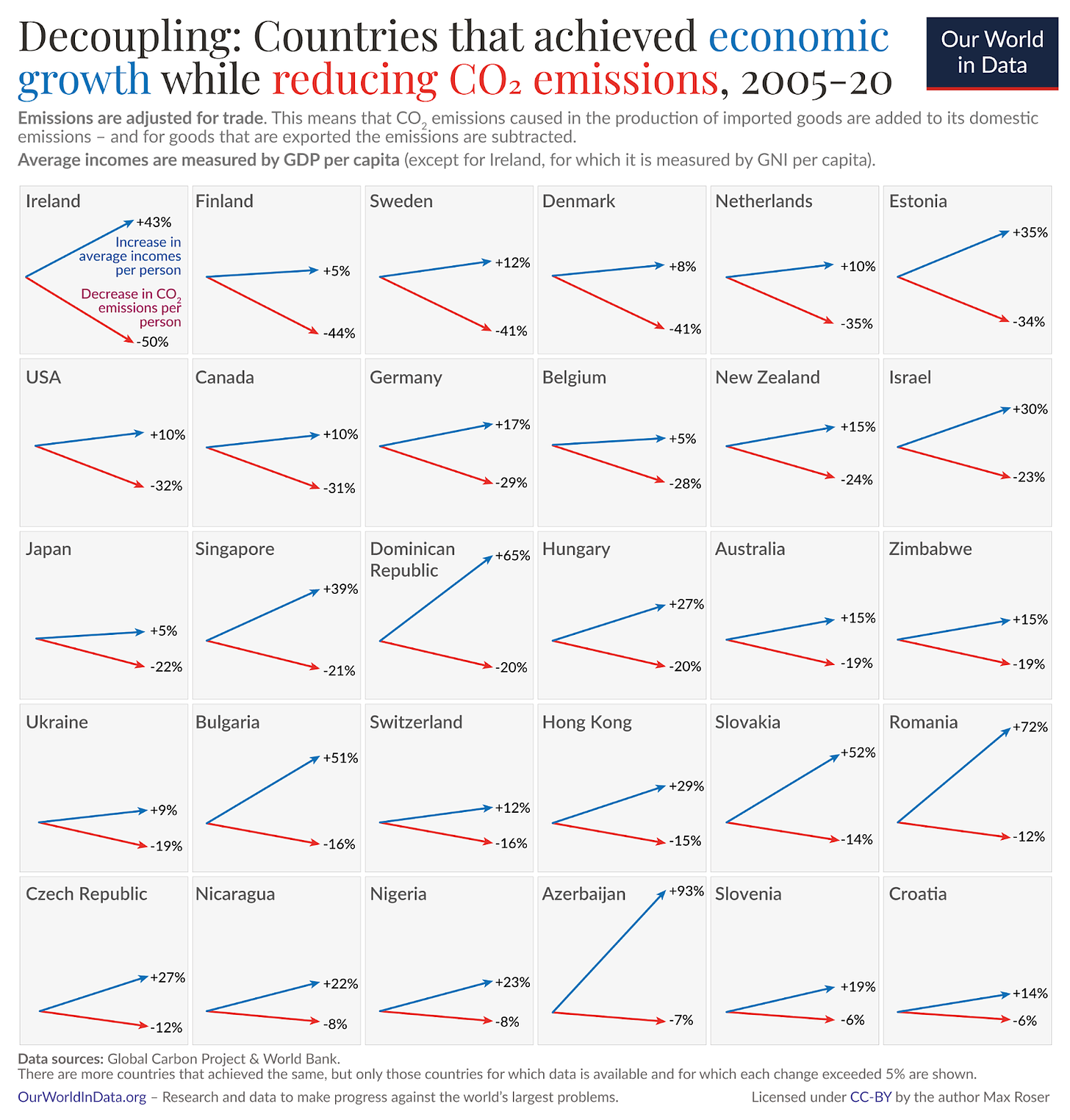

Crucially, these massive reductions have not come at the cost of economic progress; many developed countries have achieved significant GDP growth while reducing per-capita emissions.

Source: Our World in Data

Do these numbers surprise you? If so, you’re not alone.

Hannah Ritchie’s book, Not the End of the World: How We Can Be the First Generation to Build a Sustainable Planet, is full of such counterintuitive data. Not the End of the World is where I first encountered the idea that my grandparents’ generation had higher per-capita emissions than mine. I knew emissions had been falling, but despite years working in the environmental and climate space, I hadn’t internalized how far we’ve come. This is where Ritchie excels. She is a brilliant science communicator able to translate data into compelling stories that enlighten and inspire. Her book, like her writing at Our World In Data and Sustainability by numbers, is the perfect antidote to gloom and doom.

From air pollution to overfishing, she uses data to show that we’ve been far more successful addressing environmental challenges than typically reported. Ritchie’s goal is to inspire action by arming us with the data to be optimistic about what our efforts can achieve.

If we want to get serious about tackling the world’s environmental problems, we need to be more optimistic. We need to believe that it is possible to tackle them. As we’ll see in the chapters that follow, this is not a pipe dream: things are changing, and we should be impatient about changing them faster.

Importantly, and often missing from most discussions on sustainability, Ritchie makes clear that sustainability can’t be limited to environmental measures. Human well-being must be a core metric, too. Ritchie’s book is the first I’ve read in the progress studies canon that puts the interplay between environmental and human progress in proper context.

A world in which half of all children die is not meeting ‘the needs of the present generations’ and is therefore not a sustainable one.

There is no shortage of data to support the claim that things are changing for the better on both human and environmental dimensions. Here are a few of my favorite highlights from the book:

In rich countries carbon emissions, energy use, deforestation, fertilizer use, overfishing, plastic pollution, air pollution and water pollution are all falling, while these countries continue to get richer.

As recently as 1800, about 43% of the world’s children died before reaching their fifth birthday. Today that figure is 4% – still woefully high, but more than 10-fold lower.

Every day, 300,000 people get access to electricity and a similar number get clean water, for the first time. This has been the case every day for a decade.

In 1820, more than three-quarters of the world lived below the equivalent of this poverty line. Today that figure is less than 10%.

In 1990, 2 billion people lived on less than $2.15 per day. By 2019, this had more than halved to 648 million. To put this development in perspective, every day for the last 25 years there could have been a newspaper headline reading, ‘The number of people in extreme poverty has fallen by 128,000 since yesterday’.

Between 2013 and 2020, Beijing’s pollution levels fell by 55%. Across China as a whole, they fell by 40%.

Make no mistake. Ritchie is not arguing that problems don’t exist or that we can rest on our laurels. She is pushing back against a cultural pessimism that has led people to forget the progress we’ve made and give up on the progress we can yet achieve.

She addresses this pessimism directly at the beginning of several chapters by debunking popular doomsday prophecies. She is neither belittling nor dismissive - she takes the central concerns of each prophecy seriously. For instance, in the chapter on plastics, she examines the claim that by 2050 there will be more plastic than fish in the ocean. The claim is wrong, but people are rightly worried about the effects of plastics on wildlife. However, the material itself is not the problem. The problem is plastic pollution.

Time for another poll:

Globally, somewhere around 0.5% of plastic waste ends up in the ocean. The vast majority of that plastic pollution, quite small compared to overall plastic consumption, comes from middle income countries where waste management systems haven’t kept pace with economic growth and plastic use. Modest waste management investments in these countries could dramatically reduce the flow of plastic to the ocean. Yet, several US states have plastic bag bans and plastic straw bans have become a silly political litmus test even though abolishing all consumer plastic use in the US would hardly make a dent in the ocean plastics problem.2 In other words, encouragements to reduce, reuse, and recycle plastics don’t do much good.

“We complain that it has become so ubiquitous in our lives, but this is a testament to the fact that it is such a useful material.”

Plastics are amazing. Plastics are much lighter to transport than other materials (saving fuel and carbon emissions). They keep food fresher, longer (reducing food waste and emissions). They are used to make lifesaving medical devices. The list could go on. We don’t want to eliminate plastics. We want waste management systems that eliminate plastic pollution.

Like in many environmental stories, the real problem is misidentified or misrepresented, resulting in proposed solutions that are inadequate and require unnecessary human sacrifice. They seem to be more designed to satisfy a narrative than to solve the problem.

Ritchie is persuasive because she avoids these traps. She has an obvious commitment to environmental causes combined with a willingness to go where the data leads. As she references several times in the book, she believed in the classic, apocalyptic environmental narrative as a student. But after looking closely at the data, she realized that humans, and the environment, are doing much better than she knew.

When I zoomed out and saw these trends, I felt stupid. I also felt cheated. I had been duped by an education system that was supposed to teach me about the world. I was a diligent student. I won medals for coming top for everything from earth materials to sedimentology, atmospheric science to oceanography. I could create complex diagrams of seismic faults, I could recite the chemical formulas of pages of minerals from memory, but if you’d asked me to draw a graph of what was happening to deaths from disasters, I’d have sketched it upside down.

This sets Ritchie, and the book, apart from the typical antagonism of partisan environmentalism - where opponents argue an issue is either existential or doesn’t exist. She paints a beautiful portrait of what progress has been achieved while still being a call to action to address the blemishes that remain.

Not the End of the World is an important book, and one I hope quickly becomes required reading in environmental curriculums. It is a vision for the future, grounded in the progress of the past, that is desperately needed. Ritchie urges us to get to work and reminds us that solutions exist or can be found. Instead of a world where people question whether to have kids lest they live through or contribute to a climate catastrophe, we should recall that in many ways we’re better off than our grandparents. We should expect that our grandchildren will look back and say the same.

Thank you to Julius Simonelli, Rob Tracinski, Steve Newman, Kevin Kohler, Quade MacDonald, and Brendan Mulligan for their edits and suggestions.

On a per-capita basis: https://ourworldindata.org/co2/country/united-states

North America and Europe contribute roughly 5% of annual plastic emitted to oceans combined. Shipping plastic overseas isn’t a big contributor either.